Interior Scholarship | Blog 02 | _(IR)RECOVERABLE RUIN_ | Catalina Dumitru [english]

I am fascinated by the life cycle of built environment. No matter how durable it was intended to be, everything is degrading. Despite our historicist sensibility that will not allow us to erase the past without feeling a little barbaric, despite our bravest hopes to preserve everything, I find it unnatural not to accept destruction. Degradation, yielding to the natural law, becomes a source of mystery and beauty, exactly because we cannot know about what lies beyond death.

In this sense, every building is an incipient ruin. From the moment of construction, ruination starts. The architectural problem begins when the building no longer respects the principles of order. The windows become openings; the walls do not impose strict divisions on the space; new ways of perceiving the interior suggest themselves. The building becomes risky to explore; spontaneous scenarios of space open. Without rules, the space offers a “happening” — it questions and redefines intentions, identity, built architecture itself.

A ruin is on the verge or threshold between form and formlessness, as well as between inhabitable and uninhabitable. It lends itself well to a deconstructionist interpretation that would not view architecture primarily as a shelter and refuge. Without a sense of utility, then, does a ruin properly belong to the sphere of art? Or the manifesto, even? This is an open question that my project will keep returning to.

To tackle this complex topic, I am going to focus on something specific. I am not going to discuss the Romantic fascination with monument-ruins. I am going to focus on an abandoned power plant that is part of the post-industrialization landscape in Romania, where entire industries disappeared and left behind buildings that remain, to this day, in a state of steady ruination or have been demolished and replaced.

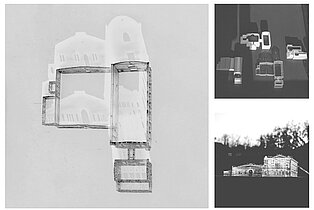

The power plant was built in Florești, Romania, in 1922-23. It was commissioned by Steaua Electrică to generate electricity to power the oil refineries in the petroleum-rich surrounding area. It was built by the architect Duiliu Marcu and the engineer Emil Prager. The design was heavily influenced by the Neo-Romanian style, a historicist style using traditional motifs developed mainly in the late-19th and early-20th centuries in Romania. The reinforced concrete structure was covered over with red brick, which is decorated by ornamental cornices, enframements, and pediments. The power plant closed in 1971, and it has been falling apart ever since.

I present three main ideas that problematize the ruin as an architectural phenomenon. My case-study is the power plant.

One: Architecture in its basic form separates the exterior from the interior. Interior architecture is usually contained within the limits defined by the exterior shell of a building. But a ruin often does not present a tightly sealed space. In that case, how is interior space to be defined?

Two: If architecture is a form of coherent organization that expresses an identity and an idea, then what does a ruin express through its unexpected rules and lack of organization?

Three: Adapting a building to a novel purpose, context, etc., without depriving it of its identity is a general problem in architecture. With ruins, the problem is especially relevant. Usually, working with existing buildings tends to result in a form of facadism. How can working with ruins provide new insight into working with the past?

We mean by ‘tabula rasa’ not only demolishing a building but turning back the clock to a certain initial point. It is separating the natural progression of the history of a building from its identity.

If rehabilitation can be defined as the resumption of possession of a building, then a ruin, before any process of rehabilitation, is without any owner. It is space that is left alone, simply to be.

How can an architectural intervention let the past coexist naturally with the present?

In my project I want to analyze how nature takes over architecture. The ruin becomes more empty space than built space. It is about the shell, and the void enclosed by it. What does the absence, this surplus of space create? How can we shape this void? What scenario can we imagine for occupying a ruin?

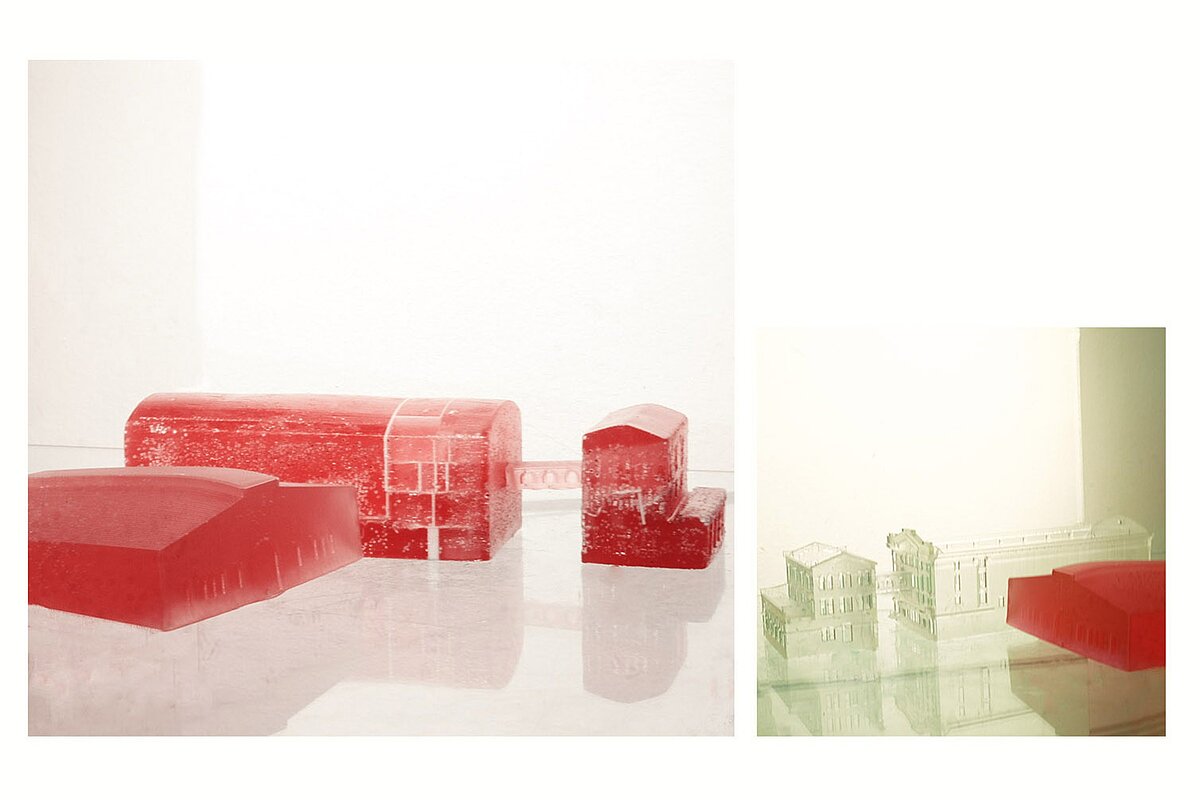

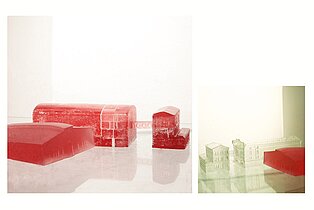

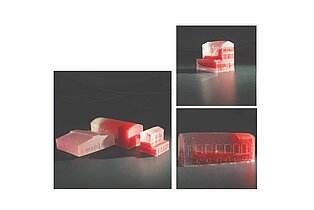

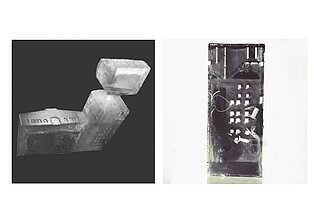

Pursuing this concept, I explored techniques as resin printing, silicon moulding and resin casting. My first idea was to materialize the empty space. But what material would express best the tactile, full sensation of being in a certain space, but also the emptiness of space? I decided to use resin. I turned the empty space into a solid block of resin. I have made the void visible. On the other hand, I reduced the façade to a fragile boundary, because, in our experience of a ruin, it is the empty space that is significant, not the built space. I have turned into tangible material the experience of a ruin.

Ruins offer not only a physical experience for the senses, but also material for the imagination.

Every ruin served a particular purpose in the past, then stopped doing so. Its lack of a function, its disregard for utility, allows for a pure experience of space. Even the most pedestrian activities gain a significance when taking place in a ruin. A ruin is a setting for spectacle and for making suggestive associations. Just as dead things are strange, but in their strangeness fascinate, ruins are mysterious, sinister, and enthralling. There is no clear resolution, because a ruin has already been resolved, in a way, in a kind of death. There is no clear pattern, as it becomes riddled with gaps and distortions. The lack of pattern creates new associations.

The experiments were made possible by the kindness and support of professor arch. Andreea Iosif.